- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Marked adobes and the organization of work in Moche society

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Carlos Zapata Benites

By Carlos Zapata Benites

Moche society developed between 100 AD and 900 AD, approximately. It covered a wide territory along the north coast, ranging from Piura in the north to Nepeña in the south (Castillo and Donnan 1994, Castillo and Uceda 2008). Within the cultural expressions of Moche society, its great and majestic stepped pyramids with their polychrome murals that present mythological beings from the Moche pantheon are well known.

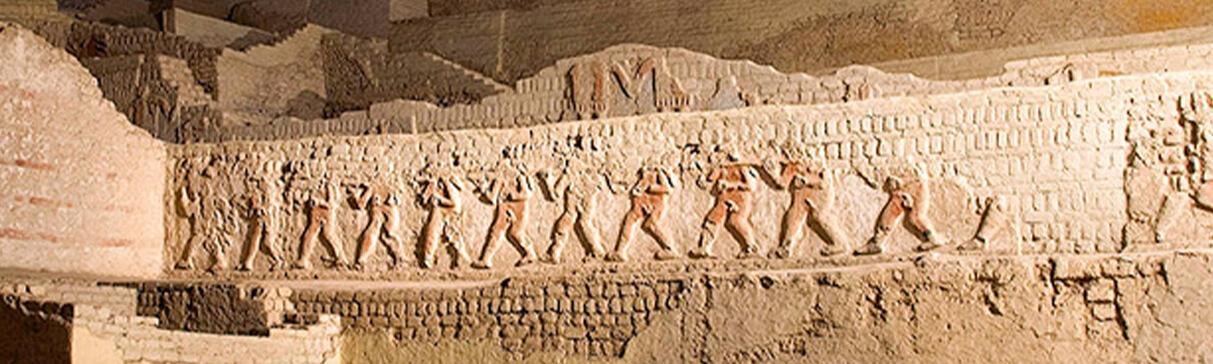

Façade of the main square of Huaca Cao Viejo. One can see the large number of adobes used in the construction of an edifice measuring 120 m on each side and 30 m in height.

In a highly hierarchical society such as the Moche, we have been able to identify personages who were at the head of society, such as the Lord of Sipán (Alva 1992, 1999) or the Lady of Cao (Franco 2008). But have we ever wondered: who built the great Moche pyramids that astound the world for their architectural and aesthetic quality? Who built these temples where the most important Mochica personages were buried?

The Moche Step Pyramid Builders

In the capital of the southern Moche state, in the valley of the same name, the construction of the Huaca del Sol edifice included the use of 143 million adobes and that of the Huaca de Luna temple some 50 million adobes (Hastings and Moseley 1975). Thus, throughout the entire Moche territory we have edifices of similar or larger dimensions, such as the Pampa Grande, Galindo or Huaca Cao sites, among other Moche sites.

Thinking about these large dimensions makes us reflect on the great capacity of the Moche State to mobilize the workforce of its population and that these large quantities of adobes have been produced by Moche settlers, anonymous in history. However, archaeologically, in Moche society there have been traces of communities or family groups that have contributed to forging and building not only the great temples and buildings, but also society itself.

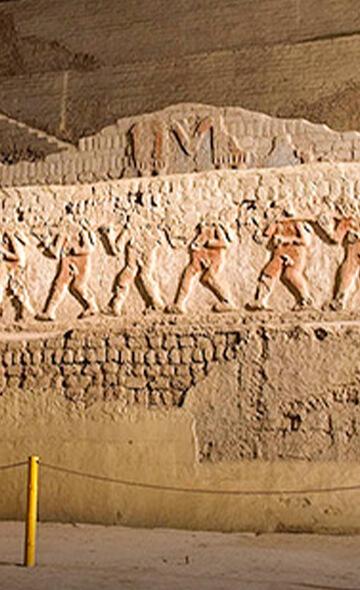

Marked adobes in Moche constructions

Let us think of Moche buildings as a space under continuous rebuilding, with an architectural history that presents different construction phases. Each of these phases involves the rebuilding and sealing of a previous edifice. Thus, with each construction phase a previous edifice would be covered and a greater volume would be gained. Archaeologists have identified that the construction technique used to seal the edifices consists in the arrangement of “interlocking adobe blocks” (Kroeber 1930: 130). Said blocks are made up of groups of adobes that have a mark on their surface, which would be the mark of a community or "manufacturer's mark."

These “manufacturer's marks” have been documented in Moche sites such as: Huacas del Sol y de la Luna (Hastings and Moseley, 1975), Pampa Grande (Shimada, 1994), Galindo (Lockard, 2008), Huaca Vichanzao (Pérez, 1994), Dos Cabezas (Donnan, 2007), Huaca Cao (Franco et al, 1994), among other sites. The marks generally include geometric designs (diagonals, points, circles) and, to a lesser extent, figurative designs (animals, hands, feet, truncheons, nets, etc.). Geometric designs generally tend to be found on almost all reported marked adobe sites, but other designs may be unique and only found at one site (Tsai, 2012).

Unique manufacturers' marks found in the East Annex of Huaca Cao Viejo. They are not repeated in any other identified adobe block.

Adobe block constructed with diagonally marked adobes. Discovered in recent excavations in the Eastern Annex of Huaca Cao Viejo.

The organization of work in Moche

This construction technique of the "interlocking adobe block" and the adobes with "manufacturer's marks" gives us an account of the level of technical-architectural development and the degree of work organization achieved by Moche society.

Interlocking adobe blocks found in the recent excavations of the eastern Annex of Huaca Cao Viejo, the dimensions of the interlocking adobe blocks can be seen in the photo. These blocks are 3.50 m long, 1.20 m wide and more than 4 m tall.

One of the main reflections that we must have is why mark the adobes? This was necessary because they had to account for who produced the adobes. Another characteristic that we must note is that there is a correspondence between the marked adobes and the size of the adobes (Hastings and Moseley 1975, Tsai 2012, Franco et al. 1994). As there were no standardized adobe boxes, each community or family group produced its own adobe molds; in other words, same mark, same size. In addition, generally, each block of adobes presents mostly adobes with a single type of mark.

If each block has the same mark, we must think that each block had been erected by its own manufacturers. Each community or family group had been in charge of the entire production process, from the production of the adobes to the erection of the “interlocked adobe block”. The communities paid with construction materials (adobes) and with work. Thus, each block built with its respective marks gave to the Moche State an account of its construction by a specific community. Such work was to be led by a Moche specialist at the construction site itself.

Diagram of the adobe and adobe-block production process, where the same manufacturer carries out the entire process.

In our recent excavations at Huaca Cao we have identified several “manufacturer's marks”. However, the blocks are not entirely built with adobe with the same mark, as has also been reported by other researchers. If neighboring blocks have different marks, we must infer that several communities or family groups were sharing the day's work. In this sense, there is cooperation and collaboration between the communities that share the activity of building a Moche pyramid and also its adobes.

The organization of work in the Andean world for its later times is documented by the chroniclers and by different ethnohistorical research. The division of construction projects based on social groups is a common practice in the Andes, where several family groups share the construction, remodeling or repair of the same edifice (Pacariqtambo, Urton, 1988). This allows us to state that from the beginning of Andean societies, until their end, and still today, the organization of work was vital.

Changes in Moche work organization

Towards the end of the Moche and post-Moche periods, the “interlocking adobe blocks” were built with different marked adobes, not observing a regularity in the same “block” (Shimada 1994, 1997). If we think that a change in the making or construction of architectural spaces reflects changes in the organization of the workforce, we should think that towards the end of Moche, and after this society, a change occurred that led to organizing work in a different way. Some archaeologists indicate that, towards the end of Moche, the levied labor system was changed and it was no longer necessary for the community to carry out the entire production process of an edifice, but, rather, the work was divided, differentiating adobe producers and builders (or adobe-layers) (Tsai 2012). This would explain why the blocks would have different types of marks, the masons had different adobes and it was not they who carried their own adobes.

Whatever the change that led the Moche to change their way of organizing, nothing will change the fact that their degree of organization and the accumulated work of hundreds of thousands of Moche settlers led them to be one of the largest pre-Hispanic States.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alva, Walter

1992 "The Lord of Sipán". Journal of the Museum of Archeology. No. 3, pp. 51-64. Trujillo Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

1999 "The Lord of Sipán and the Moche civilization." In: Peru at the dawn of the XXI century. Series of conferences 1998-1999, pp. 61-88. Lima, Editorial Fund of the Congress of Peru.

Castillo, Luis Jaime and Christopher Donnan

1994 “The Mochica of the North and the Mochica of the South, a perspective from the Jequetepeque Valley. In: Vicús, Krzysztof Makowski and others, pp. 143-181. Art and Treasures of Peru Collection. Lima, Banco de Crédito del Perú.

Castillo, Luis Jaime and Santiago Uceda

2008 "The Mochica". In: Helaine Silverman and William Isbell, editors, pp. 707-729. Handbook of South American Archeology. New York, Springer Science.

Donnan, Christipher

2007 Moche tombs at Dos Cabezas. Monograph 59. Los Angeles, UCLA Cotsen Institute of Arhcaeology.

Franco, Regulus

2008 The lady of Cao. In: Lords of the kingdoms of the moon. Krzysztof Makowski, compiler, pp. 280-287. Banco de Crédito del Perú, Lima.

Franco, Régulo, César Gálvez and Segundo Vásquez

1994 “Mochica architecture and decoration in the Huaca Cao Viejo, El Brujo Complex: Preliminary results”. In: Moche: Proposals and perspectives, edited by Santiago Uceda and Elías Mujica, 147-180. Lima, l’Institut Francais d’Etudes Andines.

Hastings, Mansfield and Edward Moseley

1975 "The adobes of Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna". American Antiquity 40 (2), pp. 196-203.

Kroeber, Alfred

1930 Archaeological Explorations in Peru, Part II: The North Coast. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Lockard, Gregory

2008 "A New View of Galindo: Results of the Galindo Archaeological Project". In: Mochica Archeology: New Approaches, edited by Luis Jaime Castillo Butters, Helene Bernier, Gregory D. Lockard and Julio Rucabado Yong, pp. 275-294. Lima, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Pérez, Ismael

1994 "Notes on the name and structure of a Mochica huaca in Florencia de Mora, Moche valley". In Moche: Proposals and Perspectives, edited by Santiago Uceda and Elias Mujica, pp. 223-250. Lima, l’Institut Francais d’Etudes Andines.

Shimada, Izumi

1994 Pampa Grande and the Mochica culture. Austin, University of Texas Press.

1997 “Organizational Significance of Marked Bricks and Associated Construction Features on the North Peruvian Coast”. In: Architecture and civilization in the pre-Hispanic Andes, edited by Elisabeth Bonnier and Henning Bischof, 62-89. Mannheim, Reiss Museum.

Tsai, Howard

2012 “Adobe bricks and labor organization on the North Coast of Peru”. In: Andean Past 10, pp. 133-169. Available at:

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol10/iss1/9

Urton, Gary

1988 "Public Architecture as a social text: The story of an adobe wall in Pacariqtambo, Peru (1915–1985)". Andina Journal 6 (1), pp. 225-261.

Researchers , outstanding news